Three product directors left the same company in 18 months. Exit interviews cited “lack of growth opportunity” and “unclear career path.” But when HR dug deeper, the pattern was different. All three had managers so consumed by execution and administrative burden that they had no time for career conversations. The managers weren’t bad people. The system didn’t give them space to be good managers.

This wasn’t a fluke. A VP of Sales had coffee with her ex-director of field operations three months after she left. The director admitted what the exit interview never captured: “I was drowning. I had 18 direct reports. I was in 47 meetings a week. I was approving expense reports and writing performance reviews at 10 PM. I had no time to actually develop my people or think about strategy.” The VP nodded. She recognized herself in that description.

That conversation represents a pattern that’s quietly destabilizing organizations. It’s not a people problem. It’s a system problem. And it’s hiding in plain sight.

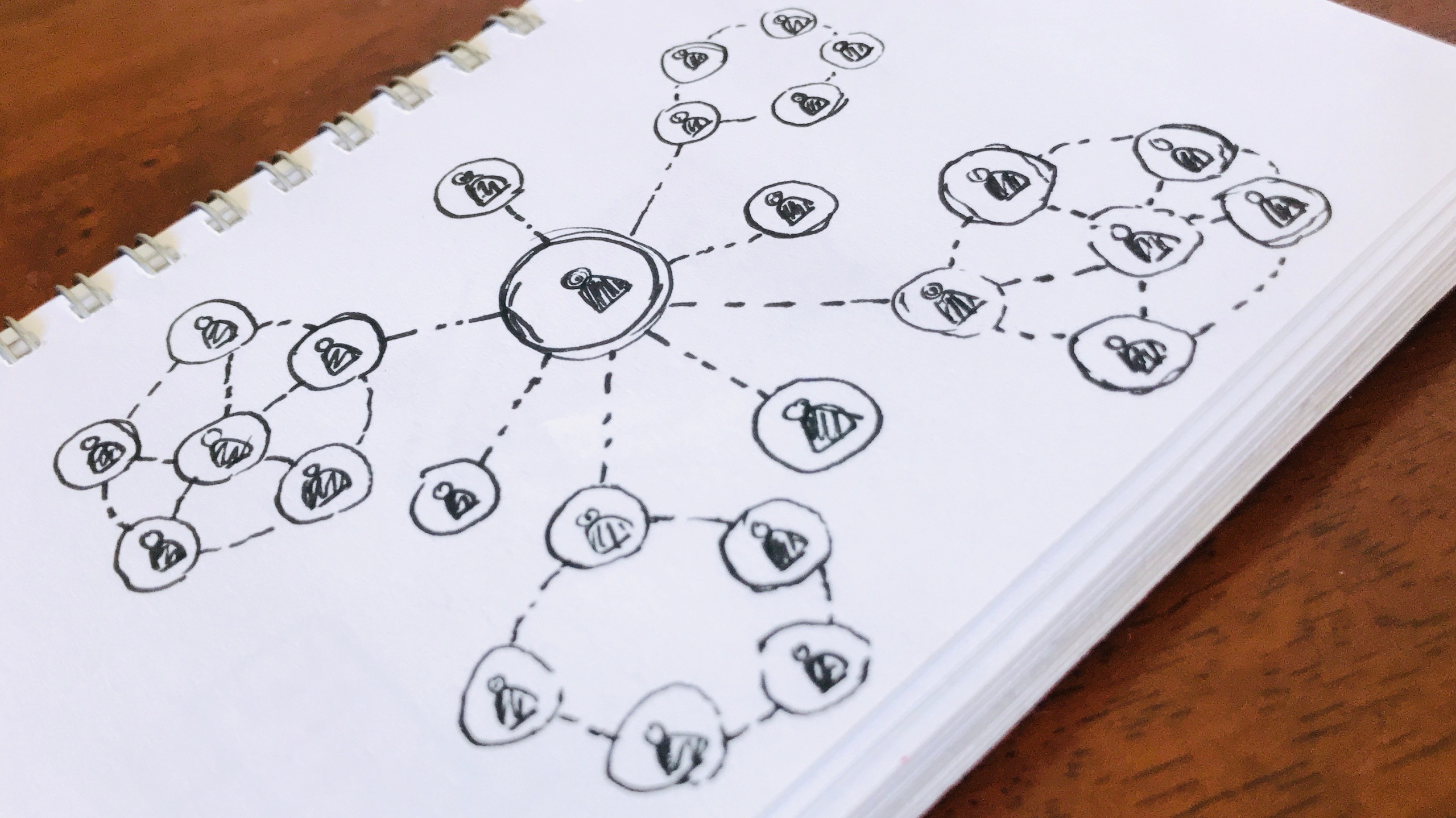

Most executives don’t think of managers as a constraint. They think of them as connective tissue—translators between strategy and execution, coaches of talent, accountable owners of outcomes. But somewhere in the last five years, the role fundamentally broke. Managers are now drowning in meetings, approvals, and administrative tasks while being expected to develop people, drive innovation, and execute strategy. They cannot do all of it. And they’re leaving because of it.

Gallup’s 2025 State of the Global Workplace report found that manager engagement fell from 30% to 27%—a decline steeper than individual contributors [1]. Managers under 35 experienced a five-point drop. Female managers fell seven points. When the people responsible for leading others are disengaging faster than anyone else, you don’t have a talent problem. You have a system that is breaking the people it depends on most.

The Impossible Job

A manager’s job, on paper, looks reasonable: hire, develop, coach, evaluate, execute, align. But in practice, especially in the last four years, those responsibilities have expanded into contradiction.

Managers are now expected to execute—hit the number, ship the product, close the deal. They’re expected to develop people—coach and grow talent, build bench strength, create psychological safety. They’re expected to think strategically—translate top-down priorities, anticipate market shifts, flag risks early. They’re expected to administrate—approve expenses, write reviews, manage compliance, plan headcount and budgets. And they’re expected to communicate constantly—update Slack channels, attend all-hands, send weekly emails, run 1:1s with each direct report.

In a 40-hour week, it’s mathematically impossible. In a 50-hour week, it’s still impossible. Most managers are running at 60+ hours a week, which means they’re choosing: they’re skipping 1:1s, deferring development conversations, or staying up late with spreadsheets.

Research from McKinsey found that middle managers spend nearly 50% of their time on non-managerial tasks—administrative work, approvals, coordination, reporting [2]. That leaves roughly 20 hours per week for the actual work of managing: developing people, coaching performance, building culture, thinking strategically. But here’s the hidden cost: that 50% isn’t evenly distributed. It’s concentrated in moments when it becomes a bottleneck. One manager becomes the person who approves budgets, which means four teams wait for a decision. Another becomes the repository of institutional knowledge, which means everyone escalates to them when something goes wrong. The manager’s calendar fills up. Their stress rises. Their engagement drops. And the people who report to them feel neglected.

The Disengagement Cascade

Gallup’s data reveals a clear mechanism: 70% of the variance in team engagement stems directly from the manager [3]. When managers are engaged, their teams are engaged. When managers are burned out, disengaged, or consumed by administrative work, their teams follow.

The 2025 report is stark. Manager engagement fell three percentage points while individual contributor engagement held at 18% [1]. That divergence is the signal. The system isn’t failing workers; it’s failing the people who lead them.

Female managers and older managers reported the steepest declines. Female manager engagement fell seven points year-over-year [1]. This points to something beyond general stress: it suggests compounding expectations. Female managers are still absorbing cultural pressure to be “more relational,” to handle more emotional labor, to manage more complex team dynamics—all on top of the same impossible job their male peers face.

The result shows up in attrition. When managers burn out, they leave. When they leave, institutional knowledge walks out the door. The people who reported to them suddenly lack a champion, a developer, a translator. Those people start looking for opportunities. Engagement drops further. Performance slips. The cycle compounds.

Why Administrative Burden Is the Hidden Leverage Point

The most fixable problem is often the invisible one.

Managers don’t leave because managing is hard. They leave because they’re not actually managing—they’re doing administrative work that someone else should be doing, or that shouldn’t exist at all.

McKinsey’s research identified specific categories of wasted time: 18% of the manager’s week on administrative tasks like approval workflows, expense reports, and compliance documentation; 14% on status meetings that could be async; 10% on rework and context-switching due to unclear decision rights [2]. Together, that’s 42% of the week spent on work that doesn’t require a manager’s judgment.

Cut that by half, and the manager suddenly has 10 additional hours per week. That’s enough time for meaningful 1:1s with each direct report. Enough time to actually think about strategy. Enough time to notice when someone is struggling.

The fix isn’t asking managers to “work smarter” or “prioritize better.” It’s systematically removing the work that doesn’t require their judgment. Automate approvals below a budget threshold. Replace weekly status emails with dashboards that auto-update. Hire an operations coordinator to handle administrative work. Reduce span of control so managers aren’t managing 18 people with 10 minutes of attention per week.

Research on span of control from a Danish hospital study found that broader spans directly predict work-life balance problems and intention to quit among frontline managers [4]. Organizations that reduced span of control from 15–18 to 8–10 direct reports saw manager stress decline and team engagement improve.

The Strategic Cost

Here’s what most boards miss: manager burnout isn’t a people problem. It’s a strategy problem.

If your managers don’t have time to develop people, you cannot scale. Bench strength atrophies. Promotions slow. Turnover accelerates. Suddenly, you’re hiring externally at senior levels, which is 3x more expensive and risky than promoting from within [5].

If your managers don’t have time to coach, quality declines. People aren’t getting feedback on their approach. Problems aren’t caught early. Rework increases. Cycle time extends.

If your managers don’t have time to think strategically, execution drifts. They’re in reactive mode, responding to the crisis of the week rather than anticipating market shifts or asking “should we be doing this differently?” You end up with a strategy that looks good on paper but meets reality that no one predicted.

If your managers don’t have time to build psychological safety, people stop taking risks. They stop speaking up about problems. They optimize for not making waves. Innovation stalls. Employee engagement declines [6].

The organizations that are pulling ahead have done something counterintuitive: they’ve reduced manager burden by investing in admin support, automating approvals, and cutting unnecessary meetings. They’ve given managers back the 10–15 hours per week needed to actually manage.

What Now

If you lead an organization where manager burnout is rising, the fix requires you to audit and redesign the role itself—not just ask better questions in 1:1s.

Audit manager time allocation. Have 20 managers across functions track their time for two weeks. Break it into categories: direct report time, execution, administrative, and meetings. If administrative work plus unnecessary meetings exceeds 40%, you have a system problem, not a person problem.

Cut the administrative layer systematically. Look at the workflows managers are stuck in. Which approvals could be automatic below a budget threshold? Which reports could be dashboard-based instead of weekly emails? Which administrative work could move to an operations coordinator or HR? Target cutting 10–15 hours per week of administrative work per manager.

Reduce span of control intentionally. If a manager has 15+ direct reports, some are getting inadequate attention. Calculate the math: 40 hours per week ÷ 15 people = 2.6 hours per person per week. That’s not enough for development. Target spans of 8–10 for first-line managers, 4–6 for senior managers. Hire the additional managers; the investment will pay back in retention and performance.

Default to async for status, synchronous for judgment. Eliminate “status sync” meetings that could be read in an email. Require agenda and pre-work for decision meetings. This alone can free 5–8 hours per week. Give managers tools to automate approvals, delegate admin work, and run tight 1:1s. Give them frameworks for hard conversations. Give them permission to say no. Most importantly, give them back the calendar space to actually do the job they were hired for.

Manager burnout is not a resilience problem. It’s a design problem. The system asked too much. Until you redesign it to ask less administrative work, less coordination overhead, and fewer impossible trade-offs, you will keep losing your best managers to burnout. And you will keep wondering why strategy isn’t executing, talent isn’t developing, and engagement is declining.

Sources

[1] State of the Global Workplace: 2025 Report – Gallup

[2] The Struggles of Middle Managers in Today’s Corporate World – Innolect, citing McKinsey research

[3] The Gallup 2025 Workplace Report Shows Engagement Is Falling and Managers Hold the Key – Inclusion Geeks

[4] Span of Control and Well-Being Outcomes Among Hospital Frontline Managers – NCBI/PubMed

[5] What High Performers Want at Work – Harvard Business Review

[6] 7 Reasons Why Companies Struggle to Retain Tech Talent – Devsu